A recent article Undermining 200 Years of Confidence in Aussie Constructiondrew many responses. Some from consumer advocates, some from suppliers complaining not just of foreign product substitution but of local substitutions driven by price, some from designers and some from industry institutions with regulatory responsibility to lift standards.

“I am writing to congratulate you on a suite of recent work,” one respondent wrote.

“It is heartening to see that your comments seem to corroborate many of the observations that we have made. However, I am also feeling rather daunted by the magnitude of the changes that will be required to raise our construction compliance to anything approaching best practice. I understand it is a veritable Pandora’s Box ‘wish list’ however a few key concerns (from your articles) that we might try to address at a broad level in our 5-year strategy are:

- Construction contracts passing responsibility to the supply chain,

- Lack of single-point accountability for specs, design, coordination of trades etc.

- Tick-the-box QA & fragmentation of supply chain,

- She’ll-be-right self certification of sub contracted works and non-adherence to manufacturer’s specifications,

- Inexperienced PMs and on-site Quantity Surveyors – low superintendence expertise,

- Low on-site availability of Australian Standards and SAI Global docs,

- Dumbing down of technical and professional association quals,

- Paucity of compulsory defect reporting or rectification requirements during or after construction, and

- Non-adherence to designed and approved specifications and routine substitution with non compliant and/or non conforming product.

I thought this was an opportunity to enlist your comment on the work at hand.”

These comments echo hundreds of similar conversations I have had over the last few years. The reality is that our industry standards and regulatory controls are the product of powerful advocacy that seems to represents the lowest common denominators in our industry. The value of Home Owner Warranty Insurance has got to be the most visible example of this, but it does not stop there. Regulations to ensure suppliers and sub-contractors get paid come up short, and in more complex situations, the industry’s customers are held hostage to wrangles over product safety and failure. The sum of the parts would seem a long way short of those from a modern industry.

In NSW, there is even a levy to cover the defects liability period for multi-unit developments. It’s not that there are not insurance bonds and product warranties all paid for by the consumer, it’s just that their integrity is undone by the risk adversity of an industry that wants no blame or accountability.

But there is now a bigger picture. It embraces the reality that today’s construction is made up of many parts and those parts come from many places.

While traditional industry standards and compliance regimes are struggling with construction’s domestic shortcomings, they have not anticipated how these and similar challenges in other markets may be addressed when sourcing from elsewhere. They have not imagined how future construction contracts will need to adapt to the on-shore and off-shore procurement of tomorrows projects. Fundamental to those procurements will be how the key construction surety underwrites for performance, conformance and delivery will be arranged. The construction industry’s current fragmentation and risk aversion will need to be displaced by modern alternatives. Understanding modern construction principles is a way forward.

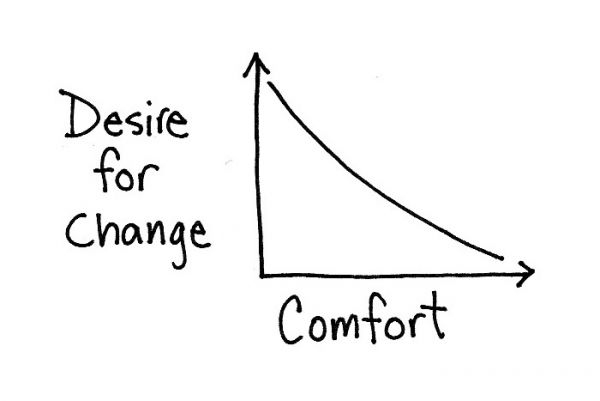

Trying to lift the capability and compliance of the whole industry at the same time will not work. That is what existing regulations and project governance aim to do, and they often do so poorly. Trying to raise the whole ocean through a legislated framework can only tackle the minimum compliance levels. Enabling tomorrow’s leading constructors to break out, to be different and thrive, must be motivated by a different approach. It must be about providing the industry’s clients a choice to differentiate between the leaders and the rest. It’s about embedding a culture in tomorrow’s construction industry that, “it is the sum of the parts that will break through.” It’s about building public confidence in those constructors. These principles are the heart of modern construction.

Modern construction practices must be different…measurably different.

To succeed in tomorrow’s global construction marketplace, constructors will need to plan on a collaborative, digital and industrialised recalibration of what they have done in the past. To perform smarter, better, work safer, faster and deliver better value for money. Embracing these trends will not be optional. Amazing new opportunities await the early movers, but those who fail to adapt will inevitably fall away. Responding is no longer a single jurisdictional choice, as construction sourcing is now multi-jurisdictional and influenced by new trade agreements and open market access, as well as new competitors. That’s why the traditional lowest denominator approach fails.

Defining “measurably different” has challenged the industry’s stakeholders. The competing interests of construction’s parts are the primary constraint in shaping easily understood alignments that point to a more viable future. Identifying the easiest to collect data, followed by presentation of that data as the most potent pointer to what “measurably different” is, must be the starting point. Multiple industry regulators should be taking note here as well. I propose the following targets:

- 20 per cent reduction in the initial cost of new built or repurposed assets

- 30 per cent productivity improvement in the use of on-site workforce inputs

- 50 per cent reduction in on-site injuries and lost time

- 40 per cent reduction in the overall time, from inception to completion of projects

- 50 per cent reduction of on-site produced construction waste going off site

- 80 per cent improvement to constructed quality and compliance

- 30 per cent reduction in the embodied energy used in constructing new assets

- 50 per cent reduction in operational greenhouse gas emissions of constructed assets

- 30 per cent reduction in 10-year projected asset maintenance costs

- 50 per cent reduction in the trade gap between total exports and total imports for construction products, materials and services.

Savings of $200 million for every $1 billion in future construction spend should be envisaged from better quality projects going into service faster and smarter. But all the parts must be measured.

The reality is that unless you can measure the benefits of tomorrow’sconstruction, there are no benefits. There is little purpose in measuring the parts without being able to draw these together to measure their sum. Unless those in positions of influence can receive and interpret the measures they can do little to make the case for change or prioritise actions to achieve “better” in the future.

There is little value in trying to negotiate or legislate industry-wide measures as the new minimum performance standard. Conflicting interests and misconceptions inhibit this. Its best to provide those with the most to gain a line of sight to achieving or delivering better, and being recognised.

There are three areas where consistently collected and presented measures will enable those in positions of influence and the most to gain, to be most usefully served. They are:

- The pre-construction phase – points to the client intermediary of record performance

- The construction delivery phase – points to the constructor of record performance

- The post-construction phase – points to the value for money performance of both

Here the challenges that all projects are different and that it is hard to compare the performance of one more complex project with another can be unpicked. In effect, the performances of projects of similar type, scale and complexity tend to cluster. It will be the correlation of this data that will allow clients, industry and governments to track future construction effectiveness trends in and across jurisdictions. I am hopeful that some new work in this area at Western Sydney and Newcastle Universities will trail blaze in this area. I am heartened that several constructors are also interested.

Specific performance outputs that could be available subject to suitable protocols may include:

- Industry peer performances around a specific project type, scale and complexity

- Trend performances of particular project types in differing jurisdictions

- Pre-qualification of consultant of contractor based on peer and sector benchmarks

- Consultant or contractor trend performance versus peers

The competitiveness of – and reward for – the early adopters of measurably improved modern construction practice will be confronting for some. There will be no need to legislate to deal with the underperformers; their future prospects will dry up in an industry where clients are able to make better informed choices. Succeeding in modern construction’s digital, industrialised and global future for those who want to come in, and stay in, tomorrow’s construction industry is a choice. It requires no new legislation. It requires those who want to be different to evidence their difference and those wanting to engage different to have credible tools to do so.

Here is an opportunity for the first 50 to 100 construction organisations who have until now whinged about clients who seem always to appoint their lowest common denominator competitors to take action to not only help the industry, but their own pre-competitive prospects as well.

The need to recalibrate the intent and substance of the industry’s performance, conformance and delivery underwrites will redefine the construction landscape. Passing on unquantifiable risk and receiving back uncertain sureties will be amongst the major drivers of change from measuring performance. The industry’s customers have had enough.

Construction’s clients have become less informed of the construction process over the last 20 years. This is a product of both public and private organisations driving overhead reduction and turning to outsourcing their once in-house skill sets. The industry’s regulators have been on a similar journey, to a point where they too are under-resourced and short of talent. The industry has become self-facing and has mostly lost the primacy of customer first. Construction procurement based on unquantifiable risk allocation and post bid margin compression will have to give way to more collaborative and value driven exchange.

A modern construction industry will accept that its customers are not construction procurement experts. Construction’s consultants and contractors will need to resolve the gaps in their dealings. Continuing to accept that projects can be committed with material information and performance gaps will not lead to better, smarter, safer, faster and cheaper. Construction is not a gaming industry. It has a direct impact on the economy, its infrastructure and public. A lowest common denominator approach will not turn things around.

We should expect to hear more of a new approach to lifting the industry’s productivity and performance standards. This will require a collaboration amongst those who see value in being different and having independently collected benchmarks against which to assess their competitiveness. That competitiveness will not only be important in opening up new opportunities in domestic markets, it will be vital in developing economies who will depend on getting more for less.