After all, it is the new building that realizes best their ideas, hopes, aspirations, and the prospect of its being diminished over time amounts to their diminishment, as well. Most architects dislike the idea of buildings’ decay and work hard to avoid it by the careful selection of materials, systems, and methods of assembly that will withstand the forces of nature continually attacking them, chiefly those of weather. Nevertheless, there is a tendency to decay inherent in materials and systems themselves—an entropy—that no amount of care in design or maintenance can overcome. Buildings will inevitably decay, and there is nothing architects or those charged with a building’s upkeep can do about it. So, what is an architect to think or do about it?

The most common thing is to forget about it. Or, to put it in psychological terms, to deny it, much as we put out of our thoughts our own inevitable decay and extinction. We tend to proceed in life as though we will live forever, thereby remaining optimistic enough to believe what we do has some enduring value and meaning. Without this capacity for denial, most would become paralyzed by despair. If architects did not believe their designs had some enduring qualities. it would be difficult to believe in what they do. So, even the designer of temporary architectural installations believes they will endure through various forms of documentation—photos, film, even reconstructions—and thus finds sanctuary in denial.

There is, of course, another, less common and more difficult way, and that is to embrace or at least accept decay from the start.

I personally find the Romantic fascination with ruins problematic. From Capar David Friedrich to Albert Speer (Hitler’s architect and town-planner). the evocative power of ruins has worked to produce powerful emotions, often for ideological—religious and political—purposes, making the motives exploitative, at the least. As a marketing device, nostalgic emotions of loss can sell paintings and politicians and their policies, but do little to advance knowledge.

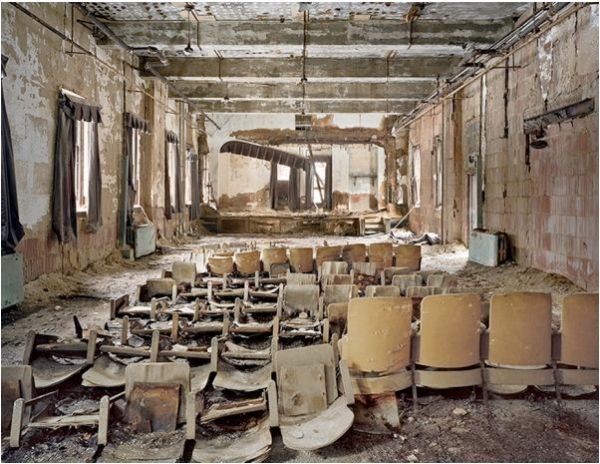

Still, there is a tougher, more critical edge to the acceptance of the decay of buildings and their inevitable ruin that places architecture in a unique position to inform our understanding of the human condition and enhance its experience. Chiefly, this is to include in design a degree of complexity, even of contradiction embodied in the simultaneous processes of growth and decay in our buildings, that heightens and intensifies our humanity. Thankfully, there is no stagy, contrived method to accomplish this in architecture. Each architect must find their own, unique way.

LW